PRAFACE

INTRODUCTION

Herein you will find a simple introduction to the language of

the Yeti people. It is meant to give you a solid foundation upon which to build

vocabulary and be able to read in the native written language and construct

basic sentences. Hopefully at the end of this guide you will be able to hold

simple conversations and by able to speak about yourself and ask questions. This

introduction will provide you with some background on our language as well as

some notes on the structure and contents of this guide.

On Structure:

This guide is comprised of six units, each with 2-3 lessons

within them. Each lesson will introduce a specific grammatical component or

focus on a set of vocabulary with a central theme. There will be two exercises

per lesson to help you grasp the material covered. Additionally, there will be

a more difficult exercise at the end of each unit for further practice and

cumulative review.

There are two examinations: one at the mid-way mark and one at the

end. Each of these will be cumulative. This is a self-motivated guide, so there

is no requirement to do any of the exercises, though they will help you become

comfortable with the language.

There will be four ways new language will be introduced to you:

vocabulary sets, grammar, important phrases, and verb conjugations.

Vocabulary sets will be shown in a blue box.

Grammar is indicated by a green box.

Verbs and Conjugations will be shown in a red

box.

Important phrases will be in a yellow box.

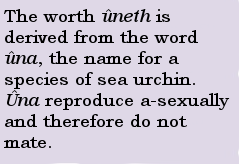

Cultural remarks will be in indicated by a purple

box*.

*(These are not necessary to know but they do enhance the

experience by providing background and context. You may skip these if you don’t

care, I promise I will only be slightly offended.)

On Orthography and pronunciation:

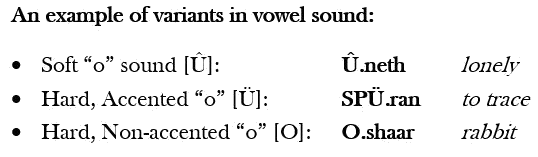

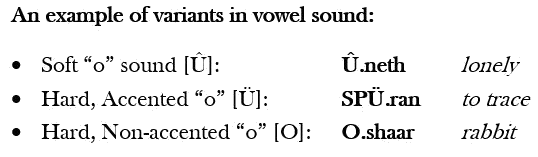

For common letters which orthographically translate to

multiple sounds, we need a way to distinguish one sound from another. For these

letters, a circumflex (Û) will be used to mark soft sounds (consonant or

vowel), in orthographic translation, to make it easier to see the

distinction without native characters. An umlaut (Ü) will be used to indicate

accented hard vowels*. There will be a table that elaborates on this in Lesson

1. Orthographic translation allows the language to be used without use of

native characters, though I strongly recommend you do not rely solely on the

orthographic transcriptions, since most texts and signs in Titania only use

native script.

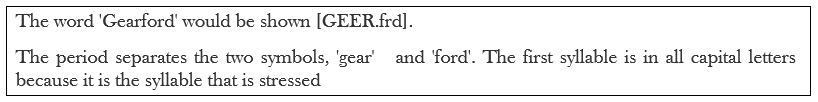

When introducing new vocabulary there will be a

standard format to make pronunciation easier. Periods in between words

demonstrate how a word is broken up syllabically. Capital letters will show

stressed syllables, for example, let's look at a word in the common

language you are likely already familiar with:

*Except for the hard A, which will be denoted by an ‘AA’ instead

of an umlaut to be consistent with the common methods of translating. See chart

in Unit 1 for details.

On Dialect:

For

the purposes of this guide, we will use the modern Titanian dialect. There are many

dialects, depending on regional and ancestral background, however, this is the

most common and wide-spread. Modern Titanian is the standard dialect taught in

schools, both in Titania and elsewhere. Since this is an introductory guide, it

will not expand upon other dialects. However, if you are curious about the

variations in some common phrases, see Appendix II.

Course Objectives

The goal of

this guide is to provide a practical knowledge base for anyone who wants to

converse in Titanian. I hope that by the end of this course, you will be able

to:

· Read

and write using the native alphabet

· Know

basic grammatical rules and how to structure a sentence.

· Introduce

and describe yourself and others and tell someone what you like or dislike

· Speak

about events or activities in the present and past tense

· Ask

and answer questions and give directions

· Express

opinions and compare things

· Conjugate

several types of regular verbs

PREFACE

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LANGUAGE

The language spoken in Titania descends from a proto-language spoken about 40,000 years ago. This was long before written records, however it is believed that the rudimentary language was common between ancient Yeti and Vibranni civilizations. As civilizations advanced, and the Yeti became increasingly isolated in the north, new distinct languages would evolve, though they share the same roots.

The proto-Yeti language that included a written component is thought to have evolved about 15,000 years ago among the small civilizations closest to the coast and mountainous regions of the north. A number of inscriptions have been found carved on loose objects. Most of these inscriptions are trade records and memorials to the dead while others, carved into stones, seemed to have been used in very old forms of folk magic. They are the oldest written records in Yeti history, and would eventually evolve into a stable set of over sixty runic symbols known now as the Aaldrsten.

This runic script was simplified in the 7th century, and inscriptions became more abundant. There was a large increase in nomadic Yeti during this time, as more began to brave the harsh inland conditions farther north. This simple and uniform set of twenty-three runes, the Ÿngrsten, became wide-spread and perhaps the first consistent written language among the ancient groups of Yeti peoples.

When international trade became more prevalent, particularly with the human civilizations, it brought along a strong influence from the language of humans. Most notably the common language inspired another revision of the runic writing system, one which created a concrete link between the written language and spoken dialects of the land. In the 13th century, a new twenty-two symbol runic alphabet system was created with each symbol assigned a specific phonetic correspondence. There have been stylistic changes to certain characters, however this is essentially the same system used today.

Titanian language forms a dialect continuum of more or less mutually intelligible local and regional variants. While the universally accepted alphabet provides standards for how to write, for much of history there was no officially sanctioned spoken language. Due to the vast size of Titania, there are numerous variations of the spoken language, all distinct though similar enough to be understood in almost any part of the country. In the 1758, the Council of Elders determined that the dialect spoken in the southeastern part of the country would be the standard used in Hjem, the political capitol, as well as the official dialect taught in schools. However, the use of any Titanian dialect is culturally accepted as correct spoken Titanian, and will likely be understood in any part of the country.

UNIT ONE

LESSON ONE: ALPHABET & PHONETICS

Alphabet – Native Characters:

The alphabet

has twenty-two different runic characters. Some of these characters represent

multiple sounds, which are denoted by a single dot or a crescent above the

character. Details about each of these diacritical marks and what they

represent will be discussed later in the lesson.

The diagram

below shows each distinct character as well as the possible marking (and sound)

it can represent. Please note that the markings are combined here for brevity,

but in actual usage a letter will never be distinguished by both a dot and

crescent at the same time.

If you would like to learn more about the

origins of the Titanian alphabet and how it has developed throughout history,

refer to the Introductory section, under A Brief History of the Yeti Language.

Orthography

and Pronunciation:

*(H,A,S): H=hard sound, no accent ; A = hard sound w/ accent; S = soft

sound

|

Character

|

Orthographic symbol

|

Sound

(H,A,S)/(H,S)*

|

English example

|

IPA symbol

|

|

A

O

a

|

A,

AA

Â

|

“Ah” ,

“Aw”,

“A” (short)

|

Cat,

Talk,

Acorn

|

æ

ɑ:

eə

|

|

I

i

|

Æ,

Ï

|

“Ay” (long),

“Aye”

|

May

Ice

|

eɪ

aɪ

|

|

B

|

B

|

B

|

Balloon

|

b

|

|

G

J

|

G,

DJ

|

G,

J

|

Game,

Joy

|

g

dʒ

|

|

E

e

W

|

E,

U,Ë

W

|

È,

“Uh”,

W

|

Get,

Up,

Window

|

e

ʌ, ë

w

|

|

V

F

|

V,

F

|

V,

F

|

Vet,

Farm

|

v

f

|

|

d

|

D

|

D

|

Dog

|

d

|

|

C

c

|

CH,

SK

|

“tsh”,

“Sk”

|

Chair,

School

|

ʈʃ

s + k

|

|

h

|

H

|

H

|

House

|

h

|

|

K

k

|

K,

X

|

K

“ks”

|

Kite

Extra

|

K

k + s

|

|

l

|

L

|

L

|

Lake

|

l

|

|

o

U

u

|

O,

Ü,

Û

|

“Oh”

“Oo”/“eu” **

“Yu”

|

Open,

Über, Boot

Unicycle

|

əʊ

ü, u:

j + u:

|

|

q

|

OO

|

“Oo” (short)

|

Book

|

ʊ

|

|

m

|

M

|

M

|

Music

|

m

|

|

n

|

N

|

N

|

New

|

n

|

|

p

|

P

|

P

|

Park

|

p

|

|

r

|

R

|

“Rrr”

|

Red

|

r

|

|

S

s

|

S,

SH

|

“Sss”

“Sh”

|

Stop,

Shake

|

s

ʃ

|

|

T

t

|

T,

TS

|

T

“ts”

|

Top,

Let’s

|

t

t͡s

|

|

X

x

|

TH

TH

|

Th (voiced),

Th

(unvoiced)

|

This,

Think

|

ð

θ

|

|

Y

y

j

|

Y,

I,Ÿ

Ĵ

|

“Ee”

“ih”

Y

|

Key,

In

Yolk

|

i:

ɪ

j

|

|

Z

z

|

Z,

J

|

“Zz”,

“Zh”

|

Zoo,

Beige

|

z

ʒ

|

** More accurately, this sound is a combination of the two

examples provided, but as it does not exist as part of Common language, and

because spoken variations are abundant even from person to person, it is

considered to be correctly pronounced using either sound or a combination of

the two.

Lesson

1.1: Alphabet Practice

Practice

writing each letter so you can get used to the written form of the language. It

might seem trivial, but it will be much easier to work on later lessons when you

do not need a reference to know what the letters are, what they sound like, and

how to write them.

Hard

and Soft Sounds:

Each letter is broken into hard, or ‘voiced’, sounds and soft,

or ‘unvoiced’, sounds. Hard consonants typically require the throat and

vibration of/near lips to make the sounds, whereas soft consonants more use the

teeth and pushing air past the lips.

·

Hard sounds encompass consonant sounds such as ‘v’,’g’,’th’

(as in the), and ‘k’ sounds.

·

Their soft counterparts consist of the ‘f’,

‘j’,’g’,’th’ (thick), and ‘s’ sounds. Soft sounds are designated by a [ ˘ ] symbol using

the native alphabet.

Accented v. Non-Accented Vowels:

Hard vowel

sounds can also have two different sounds, differentiated by accent. Accented

vowels are orthographically denoted in text by the umlaut (¨) symbol and in native characters using a single dot above the

letter (˙).

The general pattern is that accented vowel

sounds represent short sounds such as the ‘a’ in “cat” or ‘e’ in “sketch” while

the non-accented are longer sounds -- the ‘a’ in “Law”, the ‘oo’ in “loop”. You

can see the characters for each vowel and its variants in the Orthography chart

above.

Lesson

1.2: Hard v. Soft and Accented v.

Non-Accented

Are the

following hard or soft sounds?

F S O j K

Please identify

which of the following letters represent accented hard sounds

a.

A c. j

b.

U d. E

LESSON TWO: GETTING COMFORTABLE WITH

TRANSLATION

A

Few Exceptions:

As with all languages, the above phonetic rules are not

perfectly consistent, and some words may not follow this or it may not always

be clear which letter to use ( A parallel in common language would be knowing

if "F" sound is spelled out with an F or a PH). Learning this will

come with familiarity, but here are some common guidelines to follow:

· use (Ë) instead of (U) when the sound

is at the end of a word.

· most often, (Y) is used instead of (I

or Ÿ) if you can

determine a word has evolved from archaic terminology

Nearly-silent vowels will often be

dropped in translation, as in bjaarn [BjaRN] (which is

technically pronounces BĴAAr.în). Typically,

either spelling is accepted (similarly to the different but equally correct

spellings color and colour)

Most often (J) will be used for

both the ‘zh’ and ‘y’ sounds instead of using (Ĵ), especially in printed text. In most

instances, if the J comes after a liquid or soft sound, it’s the ‘zh’ sound and

if it comes after a hard consonant, it’s the ‘y’ sound.

Hjem (h.ƷEM) vs

Bjaarn (BĴAAr.în)

Lesson

2.1: Phonetic Spelling

Write your

name how you spell it in common language, then next to it write out the phonetic

spelling using the orthography chart above.

Now that

you know the sounds that make up your name, Can you write it using the native

characters?

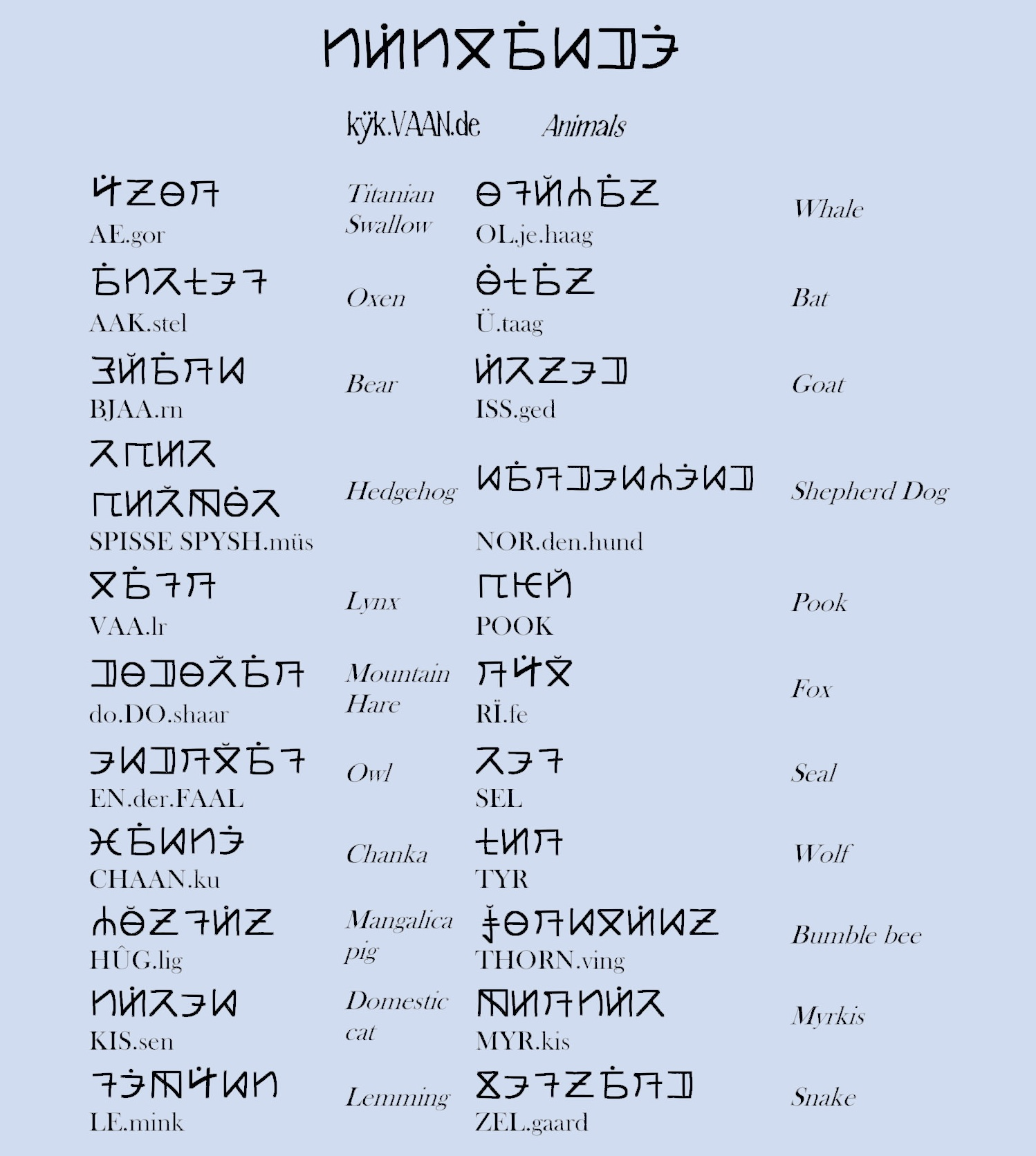

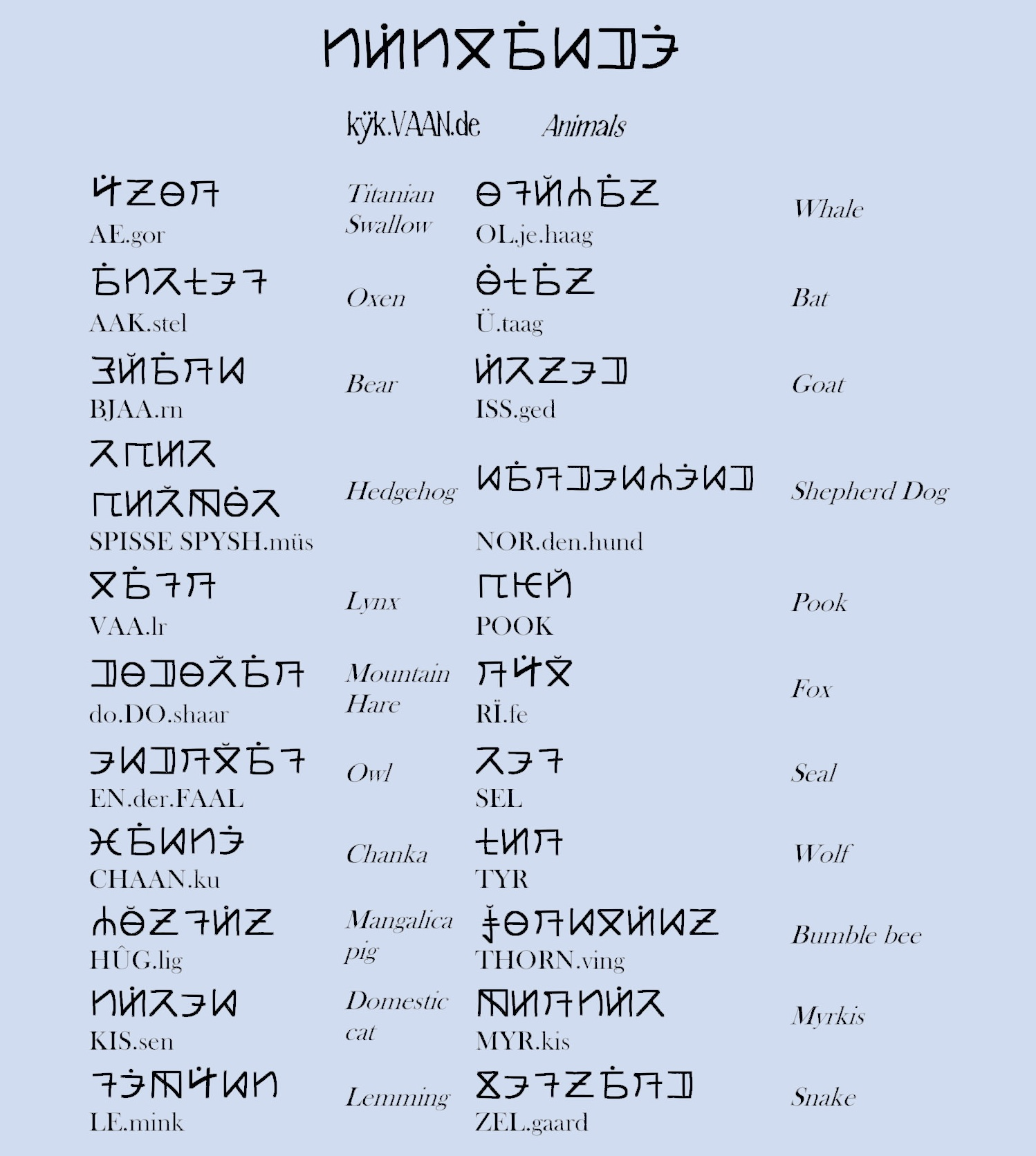

Vocab List 1: Because Who Doesn’t Love Animals?

To get familiar with distinguishing between hard

or soft, accented or non-accented letters, let’s look at the words for some of

the animals you may already be familiar with.

Use the chart above until you are familiar with

how to pronounce each word.

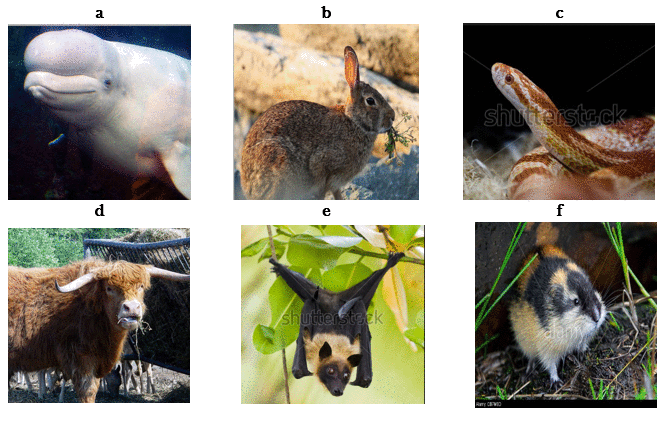

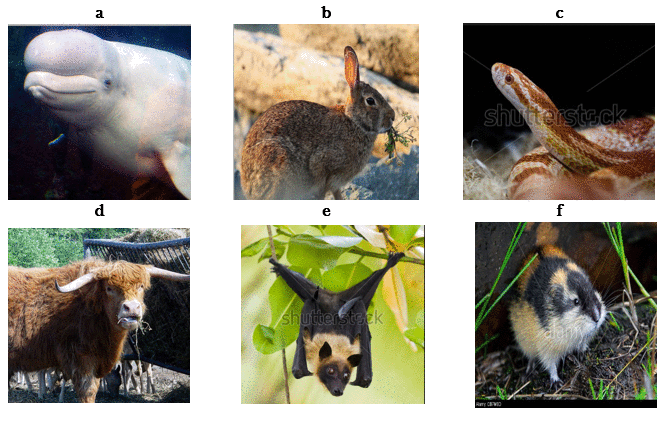

Lesson 2.2: Pronounciation

Can you

match together which 2 of these animals’ names rhyme the closest?

LESSON

THREE: WORD STRUCTURE

Syllabic

Structure:

Much like English, the nucleus of each syllable in Titanian

language is the vowel.

A I E o Y

As an example, let’s take the word GOlDAn (Gaaldan) meaning to sing.

It is comprised of two syllables, each containing the vowel A :

Gol.DAn GAAL.dan

(to sing)

The coda (the remaining part of the syllable) can be any

combination consonants. A new vowel usually indicates a new syllable.

If there are more than 2 consonants in the onset (the part of

the syllable before the vowel), one must be a liquid consonant [r, l] or [h]

DRoTYr DRO.htyr (knight )

It is not unheard of to have two stressed syllables in a row,

but it is very uncommon. Most examples of this are found in names and ancient

dialects.

Suffixes and Word Conjugation

As you will learn in future lessions, words can be modified

and gain new or nuanced meanings. There are a myriad of reasons for this, including

but not limited to: plurality, tense, and conjugations. Similar to the common

language, Titanian words are almost always modified by adding a suffix or

changing the end of the word.

An example of this can be seen when one wants to identify where

they were born. You could use the country name as the object of the sentence:

I am from Titania. TyTANje ti.TAN.jë

Or, you could change the phrasing so the country name is an

adjective.

I am Titanian. TyTANSET ti.TAN.set

The suffix -set

is added to the end of the root word Titania.

This is just one basic example. We will learn the details about such

conjugations in later lessons.

UNIT ONE REVIEW

The

following words are cognates, meaning the word shares the same linguistic

derivation and pronunciation in both the common language and in Titanian.

Please familiarize yourself with orthographic symbols as well as the characters

of the Titanian alphabet by filling out the chart below.

|

Common language

|

Titanian Translation

|

|

|

Orthographic

|

Native characters

|

|

Vibranni

|

vÿbraani

|

|

|

Gearford

|

|

|

|

|

chaankë

|

|

|

Fimbrian

|

|

fymbrYEn

|

|

|

skutlkovy

|

|

|

|

|

mOKn bOKn

|

Can you

write out the pronunciations of each of these words? Follow the form used to

indication pronunciations found throughout the unit.

UNIT TWO

LESSON FOUR: GRAMMAR AND SENTENCE STRUCTURE

Syntax – Verb-Second Order:

Conventionally, sentences are

written in verb-second order,

meaning the subject and object of the sentence (as well as any additional

clauses) can be placed in any order, as long as the verb holds the second

position of the sentence.

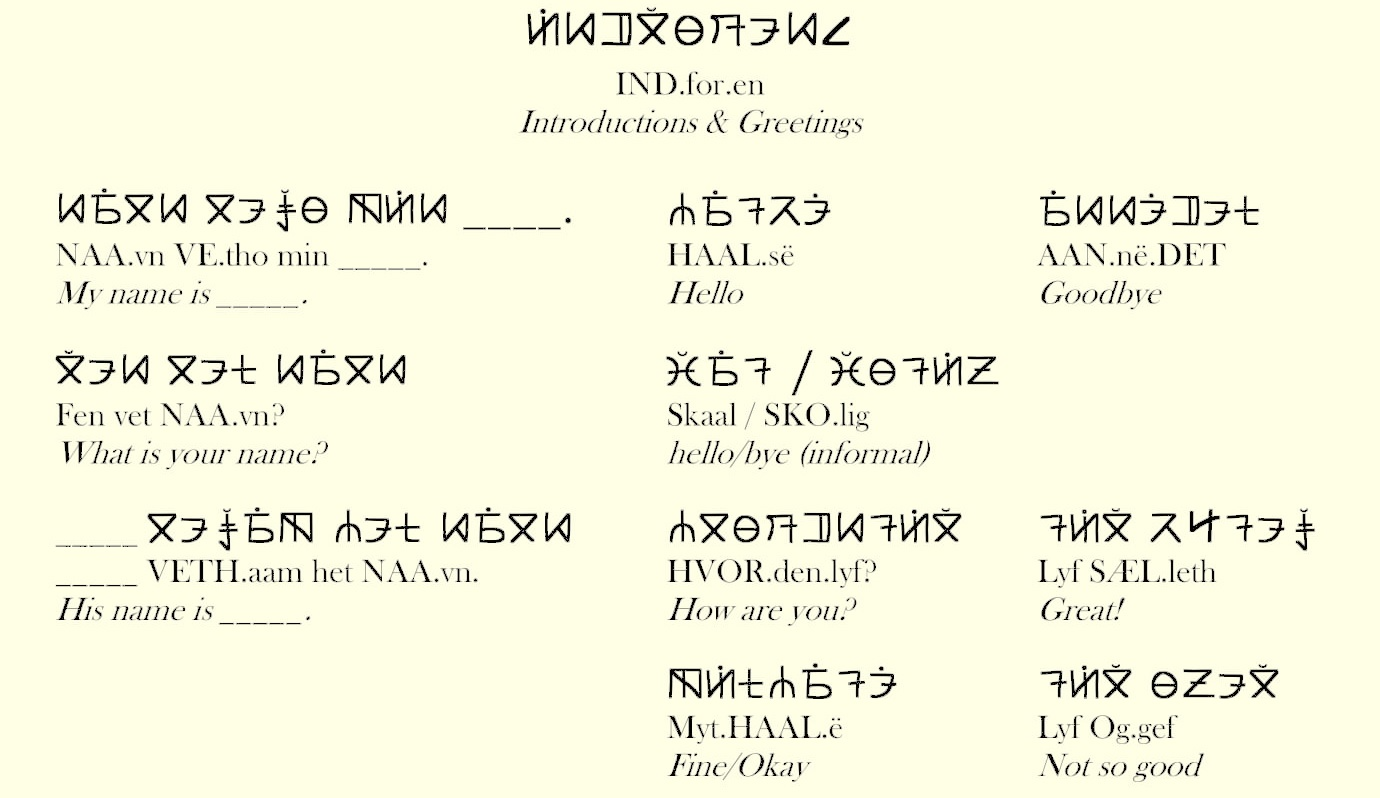

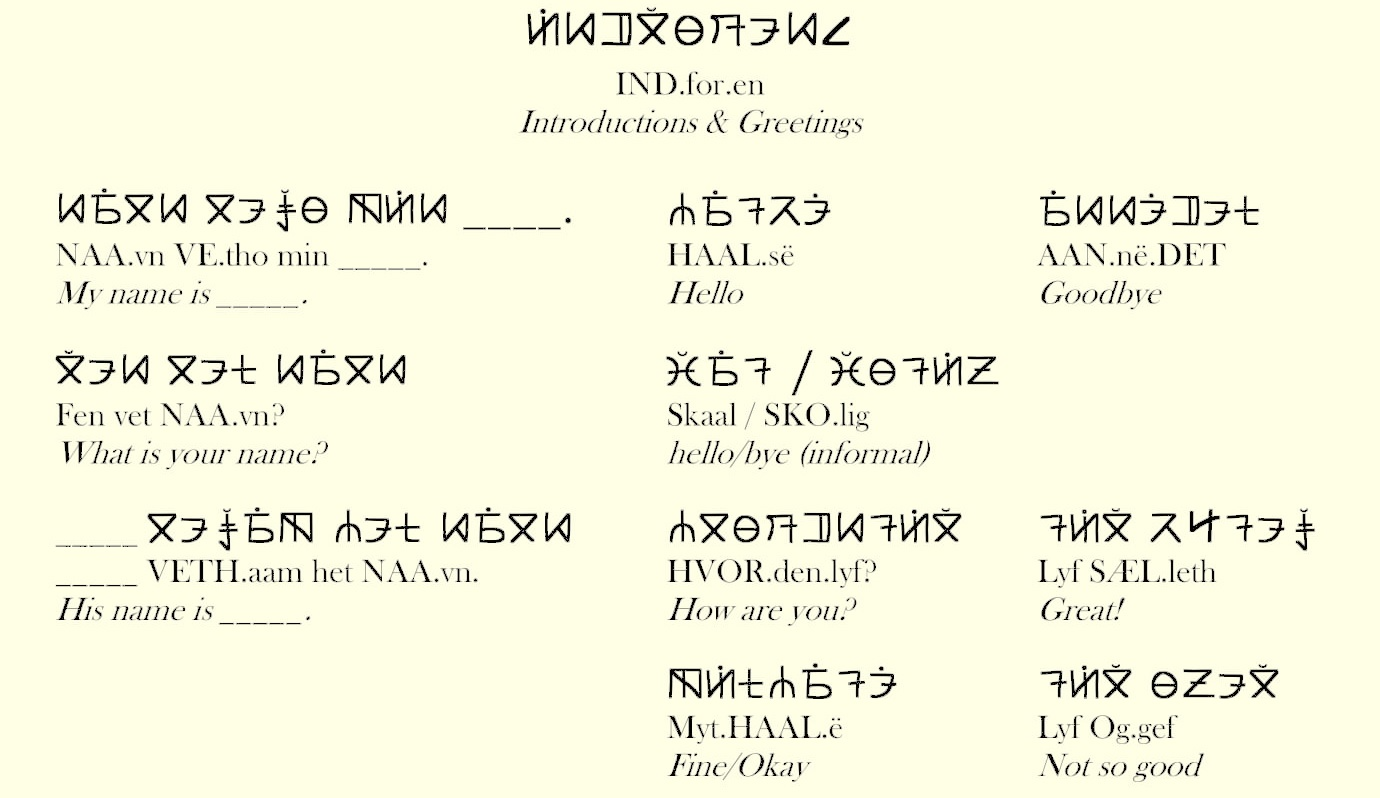

A good example of this can be seen in introductory phrases:

Examine the first two phrases

above. The verb vethaan (to be

called/named) is the second position in both sentences, though the subject, Min/Fen,

and the object, naavn, are in opposing orders.

Verb-second order is limited to

finite verbs. Infinitives (verbs in unconjugated form) and participles (a verb

used to modify a noun, such as ‘written’ in the sentence ‘Stephen King has

written many books’) do not have to follow this structure.

KySEN ET MET

HeND VEx

KÏS.sen et Met hund veth. (My dog is named ‘Kitten’).

The verb is in perfect tense, therefore the participle, ‘named’ can be

last in the sentence.

Lesson

4.1: Practicing Correct Syntax

Read the

following introductions and determine if the sentence structure is correct. If

it is incorrect, please write a correct version of the sentence below.

·

VExo MyN NOVN ASTRyD

___________________________________

·

NOVN VET fEN

___________________________________

·

HET VExOM NOVN SVEN

___________________________________

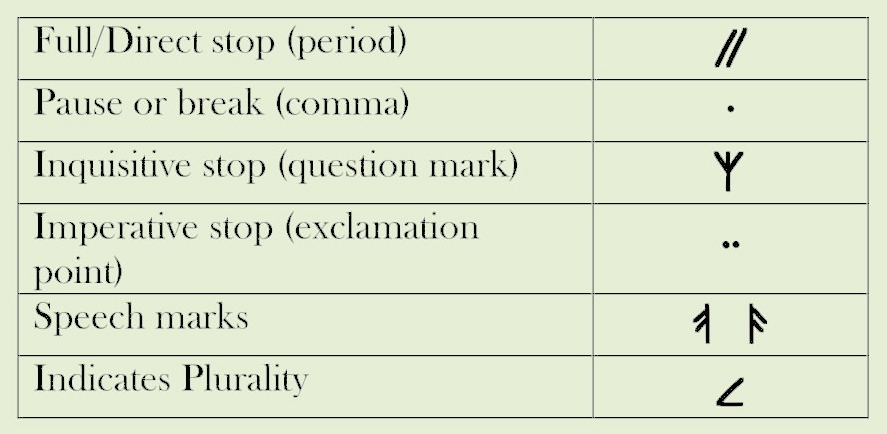

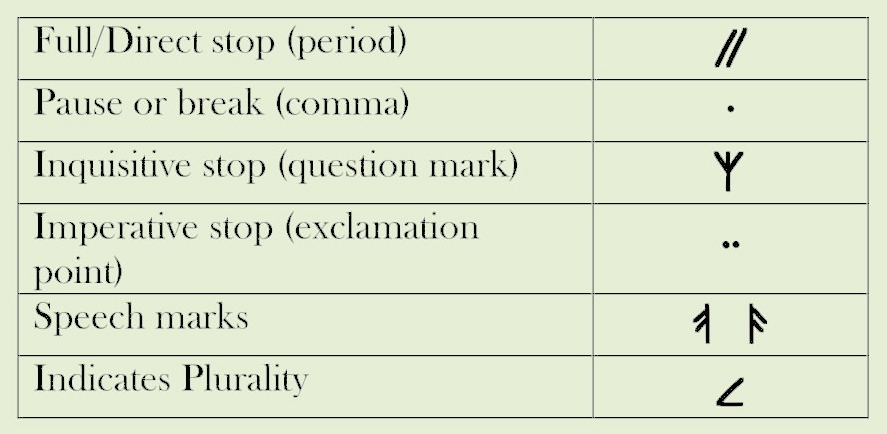

Punctuation

Now that you know how to ask someone their name and give a

response, it might be helpful to know how to indicate a interogative or

delcarative sentence as well as other basic punctuation marks.

The punctuation listed below essentially assume the same

functions as their equivalents in the common language.

The question mark ? is based on the ancient rune for

Divinity and Spirituality, which is seen as the ultimate authority to which

one would bring a query.

|

The only one that may seem unfamiliar is the last symbol. The

closest equivalent would by the ‘s’ suffix added to nouns to make them plural.

The plurality symbol works the same way in Titanian. It modifies nouns to

indicate that there is several.

Singular: Cat KySEN

Plural: Cats KySEN<

Lesson

4.2: Punctuation

Can you

write ‘My name is ____. What is your name?’ using correct grammar and

punctuation? (Note: the quotation marks around the phrase are not part of the

phrase itself, but used to dictate what should be translated.)

LESSON

FIVE: TALKING ABOUT YOURSELF AND OTHERS

Personal

Pronouns

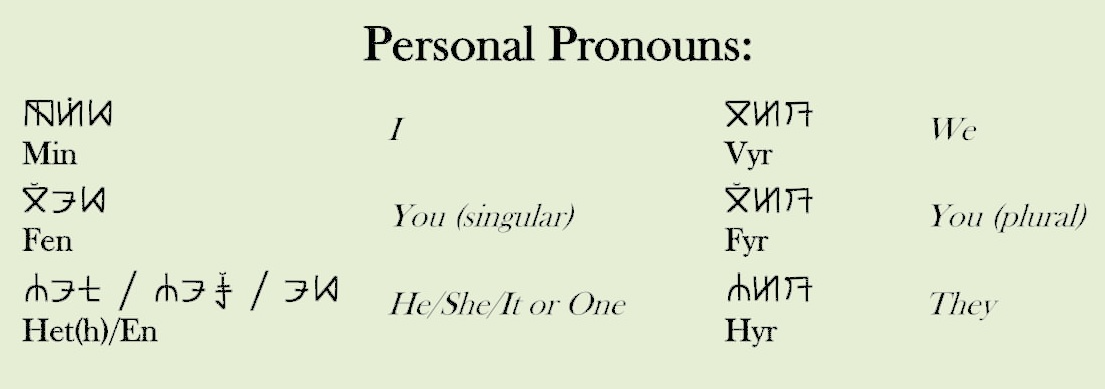

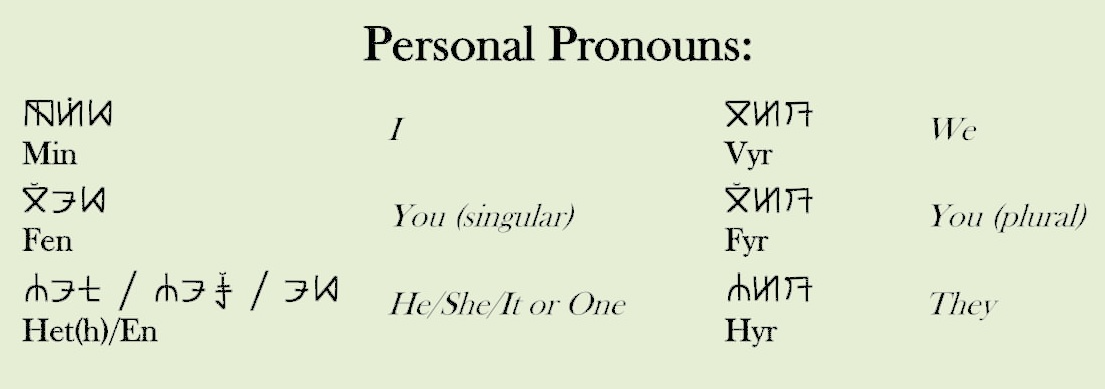

In order to properly conjugate verbs (as well as you

know…make sentences), you will need to know basic pronouns. These will allow

you to talk about both yourself and other people. Here are the six (eight if

you count each gender for third-person) personal pronouns:

Some languages have different pronounces to address someone

directly depending on their status or relationship to you (i.e. a formal and

informal equivalent of ‘you’). Titanian does not distinguish between formal and

informal pronouns.

Imparative statements (phrases that give a command) will use

the conjugations for FYR, though usually the pronoun itself will be dropped.

Name him Erik. aRyK VExyS fet.

It should also be noted that the third-person pronouns are the

only ones that are gendered, and male and female pronouns are only used for

persons based on their preference and animals based on their sex. When speaking

about objects, locations, and other nouns use the gender-neutral EN.

Lesson

5.1: Identifying Pronouns

Identify the pronoun and the conjugated verb in the following sentences.

·

HOR ES MyN.

Haar es mïn. Pronoun:

___________

(I am tall.)

· FEN VYR LON.

Fen VYR laan Pronoun:

___________

(You speak a lot.)

·

HET RosEM LUOx.

Het RO.shem LÜ.aath Pronoun:

___________

(He runs quickly.)

Adjectives and Gendered Forms:

Adjectives are generally placed directly before or after the

noun which they modify, but technically it can be placed anywhere in the

sentence as long as the verb-second form is not contradicted. The following are all correct versions of the same sentence:

BRONDLyT EM FYR HUG.

Braandlyt em

fyr hüg.

FYR EM BRONDLyT

HUG.

Fyr em braandlyt hüg.

HUG EM FYR BRAANDLyT.

Hüg em Fyr braandlyt.

As a general rule, since nouns are not gendered, adjectives only

have one ("neutral") form. There is an exception to this, however,

when the adjective directly modifies a pronoun or proper noun, it can change

form based on the gender of said pronoun.

To clarify what is meant by this, let's look at an example in

the Common Language first:

- Orla is a good lawyer.

She wins almost every case.

The

adjective, good, in this instance directly modifies the

noun 'lawyer' not the proper noun 'Orla'. The adjective would be used in a

general(neutral) form

- Max is Paorrian, but

he is also Vibranni.

Here, both Paorrian and Vibranni directly

modify Max (or 'He' if replaced by pronoun.) These adjectives would change

to a masculine form.

The plural form of a

neutral adjective will have the plurality indicator at the end, however there

is no plural feminine or plural masculine.

The neutral form of an adjective is often called the general

form or standard form, since it is

the default form of an adjective which is can be used in a general case (see

example above).

Lesson 5.2: Gendered

v. Standard Adjectives

Would the following adjectives (in standard form in brackets) be

kept in standard form or be switched to a gendered form? If it should be

gendered, what is the correct form?

aRyK LyGo ASyVOL [

ToROfSyT ]. Standard Gendered

A.rik LI.ggo A.sti.VAAL [to.RAAF.sit].

(Erik lives in the dry desert.)

MyN ES [ HiLEN ]. Standard Gendered

Min es [HÎ.len].

(I am well)

HeND [ black ] ES [ SiLEN ] HeND. Standard Gendered

Hund [BLACK] es [SAEL.len] hund.

(The black dog is a good dog.)

Most gendered adjective

forms follow a pattern: the root (or in some cases, the entire word) is kept

and endings are added; -leth is added for feminine form and -lyt for

masculine form.

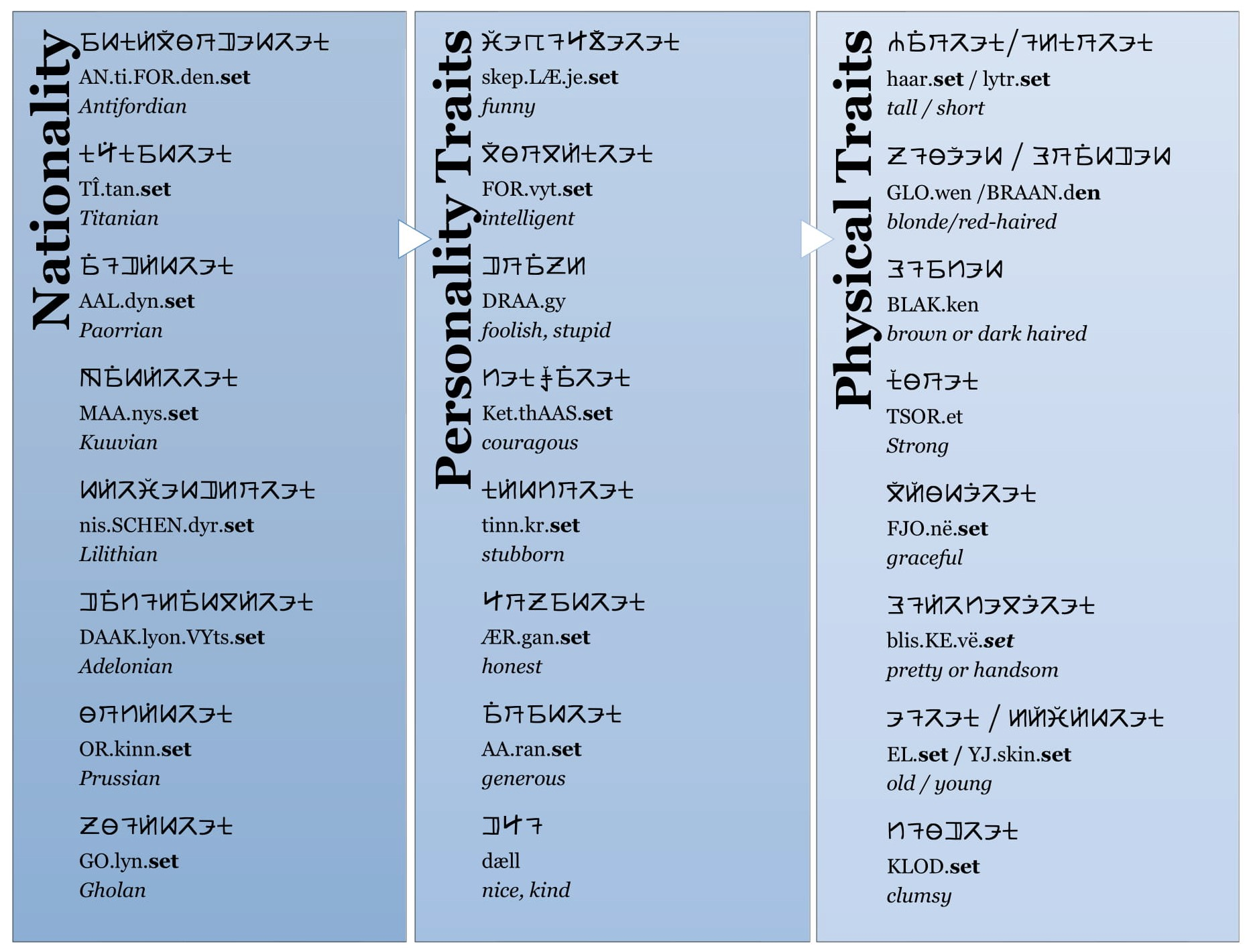

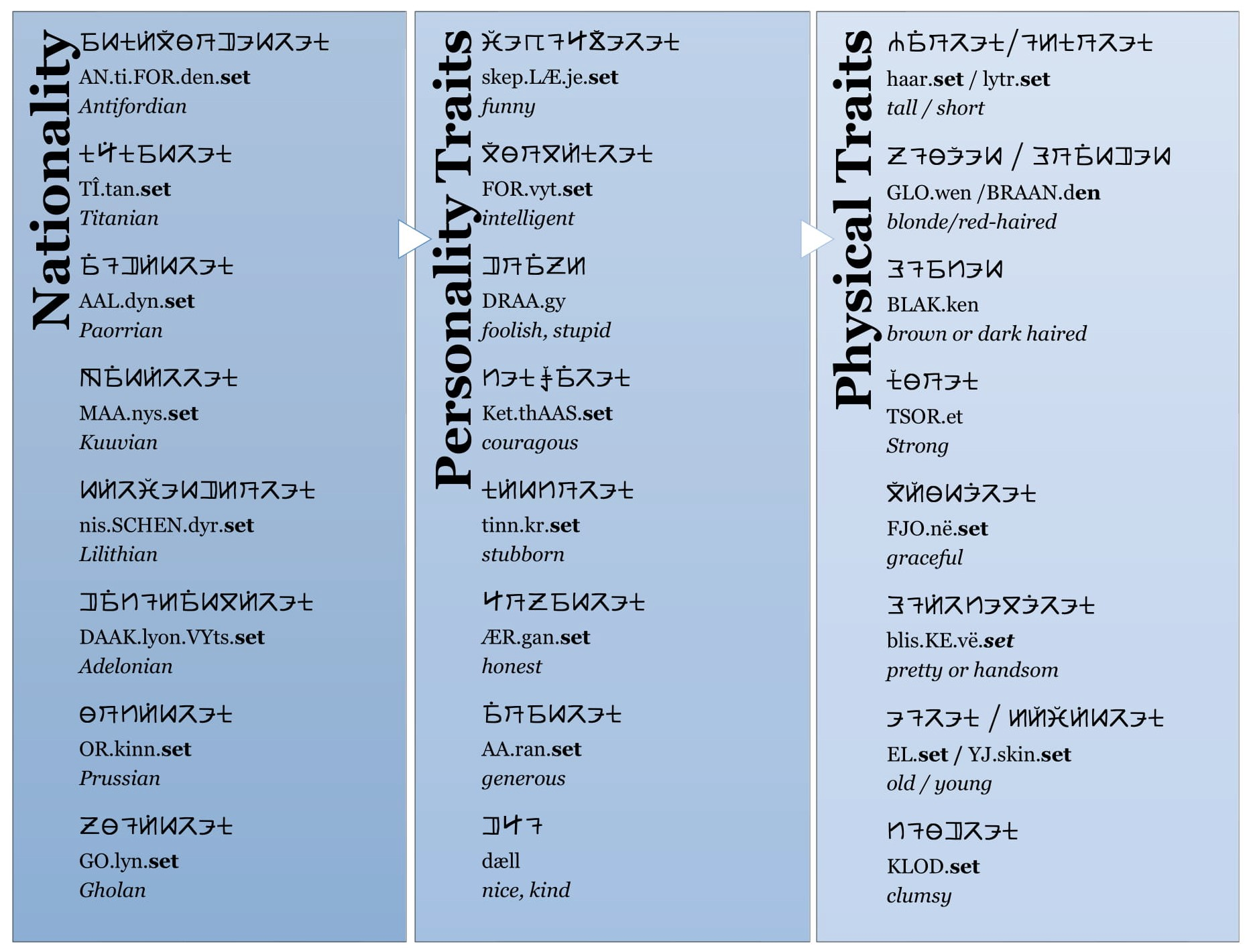

Vocab List 02 – Personal Identifier Adjectives

Let's practice with some

adjectives that follow this form. Letters in bold would be discarded in favor

of the endings discussed above. Adjectives without bold letters would just have

the endings added onto the original word.

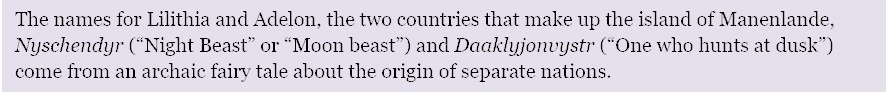

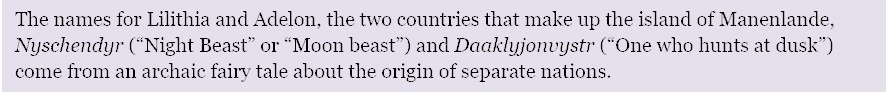

The names for

Lilithia and Adelon, the two countries that make up the island of

Manenlande, Nyschendyr (“Night

Beast” or “Moon beast”) and Daaklyjonvystr

(“One who hunts at dusk”) come from an archaic fairy tale about the origin

of separate nations.

|

Some words have the ending of the word in bold. These will change when in

a gendered form. Some adjectives, dush as DIL and toRET will not change, regardless of the subject or object it is

modifying. You will be able to recognize the former by the suffix -SET (-set) in the

standard form of the word.

LESSON SIX: SIMPLE CONVERSATION

Complete Sentences

We know how to use pronouns and how to modify adjectives for

them respectively. Now, let’s start to form some complete sentences. To do

this, we must first learn to conjugate a few verbs. Conjugation will be covered

in detail in the next unit, however we will learn the different forms of two

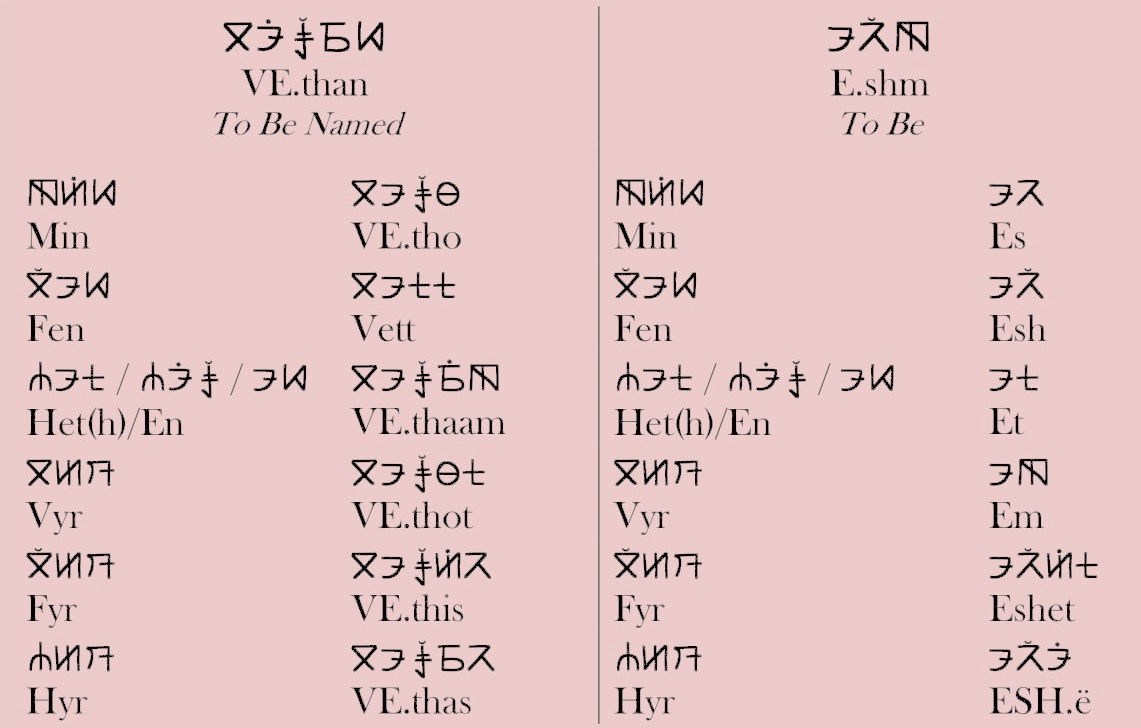

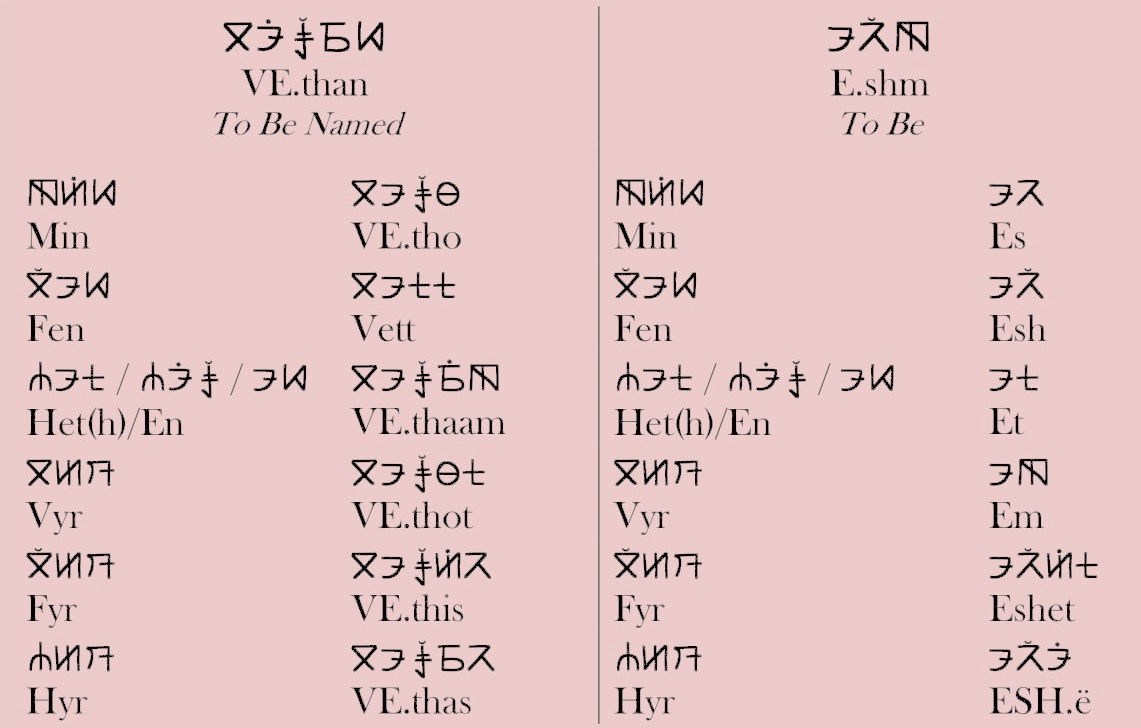

verbs that will be useful with the vocabularly learned so far: VExAN (to be called/named) and EsM (to be).

Lesson 6.1: Reading Complete Sentences

Please

translate the following sentence. Use all of the information you’ve learned in

this and the previous unit to assit you.

MyN VExo BoRyK. TiTANLyT ES MyN.

Min vetho Boric. Tîtanlyt es min.

_____________________________________________________

NOVN VETT VEN?

Navn vett fen?

__________________________________

UNIT

TWO REVIEW:

Read the

following sentences and answer the questions that follow. For this excersize it

might be helpful for you to know (YES) and (NO).

1.

ySGED et KLoDLEx. SITAN

ET HEx NOVN.

Who is being described:

Do you know their name?

2.

FYR EsET GLoWEN.

True or False: The subject(s) of this

sentence is(are) tall.

3.

oRKyNLyT ET VON KRESR.

Where is the subject from?

Is the subject masculine or feminine?

4.

goL VExo MyN NOVN. MyN ES BRycENLyT.

What can you tell me about the

subject?

5.

VYR EM IRGANSET<

True or False: We are nice.

Fill in the

blanks for this conversation.

- HOLSe

-

- HVoRDN

LyF?

-

- LyF SILEx. OrxR

VExo MyN. FEN VET NOVN?

-

- MONySET Es FEN?

-

- coLyG

-